Experience and modernity in education

Veteran and new teachers share many similarities in how they work in the classroom

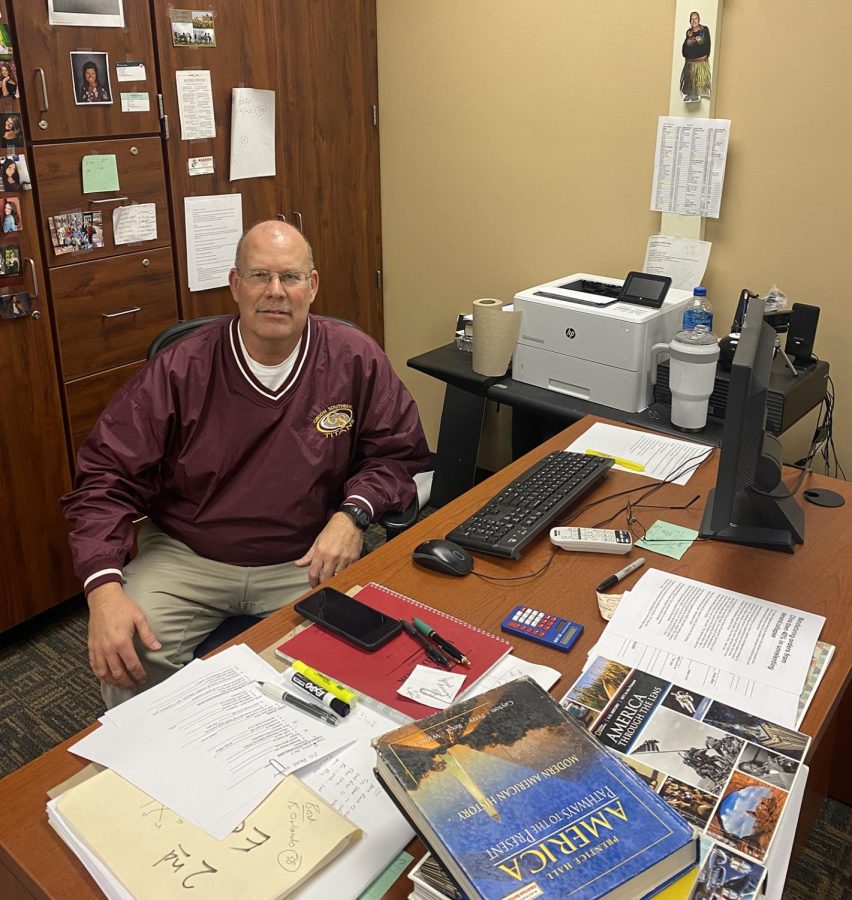

Veteran teacher Michael Priar has nearly 30 years of experience in the classroom. While his early years of teaching and training were unlike incoming teachers of today, he has adapted to the changes seen within the profession.

Gibson Southern is home to all levels of experience in regards to teachers. Michael Priar, a teaching veteran going on 30 years of experience, and Kaitlyn Mann, a fresh face who recently started her second year of teaching, are two Gibson Southern teachers who are at opposite ends of their teaching careers. With such a gap in classroom experience, how do their teaching styles differ, and how do their ideologies compare?

“I think school is much more than math, science and social studies,” Priar said. “It’s a way to help kids participate in society.”

Priar is a graduate of the University of Southern Indiana, with a degree in computer information systems (ironic since Priar now tries not to use technology and believes phones have ruined students), business administration and a master’s in education. Priar knew he wanted to be a teacher because of his love for schooling and coaching. Mann graduated from Indiana University.

“I have my bachelor’s degree in World Education and a minor in teaching English as a new language,” Mann said.

Mann started her post-secondary education in the medical field; she wanted to become a doctor. That was, until, an advisor gave her a piece of advice that changed her future.

“’Do something you like; don’t just do something you are good at,’” Mann quoted.

A large difference between these teachers’ college educations is the way they were taught to teach. Factors like technology and society and its standards caused a shift. Teachers are now expected to be personable and inclusive with students.

“We talked a lot about equity in education,” Mann said. “We had a couple of classes on reaching out to marginalized groups, including our LGBTQ students and minority students.”

This was not the case in the 20th century, when Priar was going through college. He did not have any classes on how to deal with social diversity among the student body; instead, he had to find his own method on how to handle students’ individuality.

“What I try to do, and sometimes I’m good at it and sometimes I’m not, is I always try to remember that a kid may not have grown up like I did,” Priar said. “The situation that a kid comes from at home can affect how well they do at school, and sometimes, the situation at home is more important than history class.”

The use of technology is another gap between veteran and emerging teachers. Three decades ago professors did not teach prospective teachers how to use Google Classroom or Zoom. Professors could not have predicted that technology would have become such a key component in education. Without training, many older teachers struggle to implement technology. They have to navigate it without help and take time to learn how to use it. Now, compare this to the modern education of teachers and the benefits they have of being taught how to use these tools.

“I consider myself lucky that I was still in college for that (COVID-19 pandemic), so I at least had a couple classes that talked about it (online teaching), instead of all the teachers here who never really had classes on how to teach on Zoom, or how to make a lesson on Zoom,” Mann said.

Teachers like Priar do not let their deficiencies with technology stop them from teaching students. Priar does most assignments and all tests by paper and pencil because that is the way he has always done it. He still supports the use of technology in teaching and thinks that if technology can help kids connect and learn better, then it should be used and integrated into the classroom.

“With all the technology, I think it (teaching) can be done differently,” Priar said. “I’m an old guy who has been doing it the same way for a long time, and it works for me.”

One thing both teachers went through is a fundamental part of becoming a teacher: student teaching. While it is something both educators took part in, they had opposite experiences. Priar was thrown to the wolves; his cooperating teacher walked out when Priar entered.

“I walked in on the first day, and the teacher said, ‘This is your class,’ and left,” Priar said. “We can’t do that; we’re supposed to sit in with them for so many hours and observe new teachers. They’re a lot more carefully watched than I ever was when I started.”

Mann is one of those new teachers.

“That whole last year of college, I had only been student teaching and observing kindergarteners,” Mann said. “… Mr. Adams did let me go and observe some of the other teachers in the building.”

The two teachers do share an ideology: students are people too and have their own lives outside of the classroom. Both Priar and Mann seek a connection with students, and they find it to be important that students are heard. Students feeling comfortable in the classroom leads to better participation and performance.

“It’s more important, for me, that kids want to come into the classroom,” Priar said. “Because, if students want to come in, then they are more likely to learn … if you are respectful to the kids, they will be respectful to you. You should tell them what your expectations are and be honest about what you are trying to do and teach.”

Mann’s teaching style is unique; however, she has been influenced by other teachers around the school. She had never worked with teenagers as a student teacher, only kindergartners. Mann does like to point out that teaching kindergarteners was helpful because she is practically teaching kindergarten level material to high schoolers, just in Spanish.

“I have definitely tried to base the way I interact with kids in my room off of Grigsby,” Mann said. “Working with six year olds, we can’t treat them (high schoolers) the same way … they (kindergarteners) are at a different stage of maturity, so I hadn’t seen how to treat a teenager since 2019.”

Mann will change what she has planned for a class or a due date to an assignment to make the lives of her students easier; she does this when students have important tests or quizzes in other classes. Mann is one of the few teachers who does this.

“Some people say I’m a little more lenient with due dates and stuff,” Mann said. “I try to switch quiz and test dates if I know other teachers have stuff in other rooms. From what I’ve gathered, I think I’m the only one to do that.”

In the past 30 years, education and teaching styles have changed immensely. While these changes are prominent in the ways teachers use resources like technology in their classrooms, similarities can be observed between teachers of drastically varying experience levels. While they may have had different experiences, Priar and Mann’s student teaching opportunities did teach them lessons they model in their classrooms today. They can also agree upon the fact that students are people too and deserve lenience and respect. While Mann was taught about this matter, Priar came to realize its importance through his years in the classroom. Although the ways they were taught are vastly different, teaching styles and ideologies between new and veteran teachers do often coincide.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Gibson Southern High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Camden Anslinger is a 17-year-old senior at Gibson Southern, this year Camden is the Managing Editor and a third-year reporter for “The Southerner.”...

Eva Spindler is a senior at Gibson Southern High School. This is her third year on “The Southerner” staff and is the current Editor-in-Chief. Eva spends...